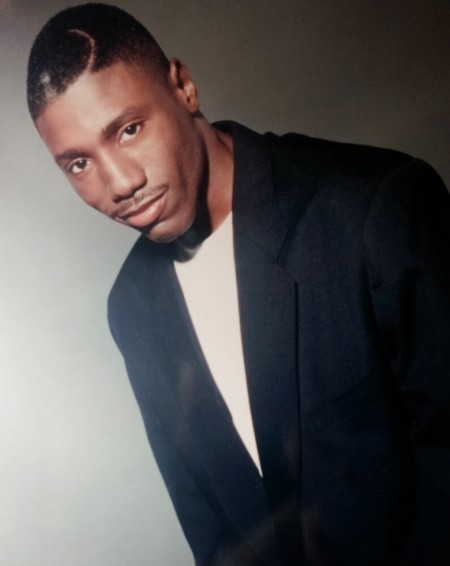

Bobby Simmons is best known as a member of Stetsasonic, the original “Hip-Hop Band,” but during an extensive conversation with him last week he also shared some classic memories about Melle Mel trolling new rappers in the late 80’s, a two-year stint as a DJ at the Latin Quarters and the escapades of Eric B. and Rakim‘s main muscle, the original 50 Cent. This is part one of a three part interview, so get comfortable…

Robbie: Did you study drumming at school?

Bobby Simmons: I self-taught myself drums, I was six years-old. My brother was in the music business too, he was a session guitarist for groups like Sister Sledge and Dan Hartman in the mid-70’s, so I kinda self-taught myself listening to a lotta the records that he would play and trying to figure out the drum – what does what. The first record that I actually learned how to play – that took me from when I was six to when I was seven – was the Ohio Players. The drummer, Diamond, I was so fascinated how he played drums on ‘Skin Tight’ and ‘Fire,’ I wanted to learn to play how he played. The drum sounds were heavy, the snare was fat, the kick was fat, and Diamond used to do all this fast foot [work] on the pedal.

From there I played in my brothers local band and just kept myself active doing that. Deejaying also helped me how to play drums too, cos in the early 80’s it helped me how to blend timings and beats, with the disco records and the Chuck Brown records and the James Brown records helped me keep great timing. Knowing how to keep timing and knowing what the kick and snare and the hi-hat do, I self-taught myself. I kinda wish I was taught and went to schooling to read for it, but my father took me to drumming school and I never went back. It was taking too long! “I wanna get to this part!” [laughs]

What was your first public performance?

The first time I played for other people was when my brother put me in his band, back in 1976. The band was called The New Experience. We used to open up for Brass Construction and BT Express, cos we all lived in the same neighborhood. They were already popular and they had records out, so for us being a local band and opening for them, it was like, “Oh, shoot!” We used to play a lot of cover songs like George McCrae ‘Rock Me Baby,’ a lot of the Top 40 songs back then.

What was the next step?

My brother was rotating the band members and I wanted to find my own thing to do. Back in ‘78 we were really in the deejaying mode, so I spent most of my time going into the 80’s doing small deejaying, not nothing big, just in the parks. Cats wanted to get on the mic, but it wasn’t really the way cats made it sound like back then, because it really wasn’t about the MC’s back in ‘79 and ‘80. It was really about the DJ. The DJ was the star. It was the MC who knew how to say the DJ’s name and give an introduction. Once guys found a way where they could do routines while the DJ extends the break of a record, we were like, “Yo, this is crazy!” When Sugarhill Records put out their first rap record and we heard “King Tim III” we was like, “Yo, what the hell is this? How do we do this?”

We were not exactly friends, but we would come back and forwards running into Flash and Melle Mel and ‘em, and Sha Rock and ‘em, when we would go uptown to watch them do their shows, or when they used to come downtown to do shows in the Village and play CBGB’s. Even though CBGB’s really was a punk rock club, they used to book rap performers early. I think the punk rock show started at 10, and they would let the rappers do their thing at 7, 8 o’clock. Bambattaa and them used to spin there and play the punk records like ‘Mickey,’ so we used to run into those guys and watch them and try to hone our craft.

Myself, Daddy-O, Fruikwan, Delite – we were actually neighborhood partners. We grew-up in Brooklyn, in Brownsville, in East New York section. Back then we were all part of the same talent events that were going on in the neighborhood. That’s when Daddy-O came up with the idea of having himself and Delite and another guy by the name of Supreme. They were just three MC’s and they were called The Stetson Brothers. They would go out and do these shows, and I used to always tell Daddy-O, “Let me DJ.” They had another guy by the name of Kid Flash who was their DJ. After Supreme left the group, they recruited Fruikwan and Daddy-O was like, “How can we find a way to extend this thing? How can we be like Parliament-Funkadelic? How can we be like Earth, Wind and Fire?”

The first person they recruited was Prince Paul. They saw Prince Paul deejaying at this party in Brooklyn and all Prince Paul saw was these three guys approach him, and Prince Paul, even to this day, he admits that he got scared. “I’m in Brooklyn, I don’t want no problems! Why are these three guys approaching me?” [laughs] DBC was recruited next. DBC’s brother, who was friends with Daddy-O, said, “My man DBC is a DJ and he also creates beats on the drum machine – and he plays keyboards.” Daddy-O’s like, “Yo! That’s dope! We could have a keyboard player and he could play live drum machines on the stage!” When I was deejaying at the Latin Quarters, Daddu-O came up to me and I said, “Yo D, we could do this live drum thing and finally do this Earth, Wind and Fire thing!” Daddy-O was like, “Yo, bet!” That’s how we came up with the concept of Stetsasonic, “The Hip-Hop Band.”

Stet was working on the On Fire album, I rarely was in the studio with them cos I had landed myself a gig. I did a tour with an R&B artists by the name of Lilo Thomas as his drummer. We went out on tour with Alexander O’Neil, the Force MD’s, then I got called for another gig to back-up Natalie Cole. I was trying to figure out a way if the Stet thing didn’t happen, at least I’ve got a good gig to back-up singers and stuff, but when the ‘Go Stetsa’ single took off, we knew something was getting ready to happen. So I had to play my cards right between the Stet gigs and the Stets recordings and the back-up drummer and recording calls I was getting with other artists.

That’s why you don’t really see my picture on the record, cos I was deciding, “Do I stay? Do I leave?” It wasn’t until the In Full Gear album that I decided – when Russell [Simmons] decided he was gonna manage us I said, “You know what? We in good hands. I’m in fellas, let’s roll!” The first record was ‘Just Say Stet,’ it got minor success. It wasn’t until ‘Go Stetsa’ was released, which got huge response, not only from the hip-hop audience but even radio. KISS-FM, which at that time was mainly an R&B station, programmed that song in their afternoon set. We was playing the Latin Quarters, we was laying the Roxy, we was playing the Fever.

Is it true that when that record came on in a club you would have to tuck your chain away?

Oh yeah. ‘Go Stetsa’ was the first record that really represented Brooklyn. Look back on the history of hip-hop, and no one really represented Brooklyn on their records the way we did, beside maybe Cutmaster DC doing a record called ‘Brooklyn’s In The House.’ Even to this day, ‘Go Stetsa’ is the most sampled hip-hop record in R&B music. People have no clue that LL Cool J’s ‘Doin’ It Well’ sampled “Go Brooklyn,” Mary J. Blige ‘Real Love’ sampled from us, and even when you go to Barclays Center, they play the chant when you watch the game. But in ‘86 and ‘87, when that record came on? The first thing you do when you on the dance floor, make sure your chain is tucked in your shirt! Because what the cats used to do when that record came in, they would form a circle around a person who they sought out who was on the dancefloor with their chain on, and they would find a good moment to get the chain. It was funny, because most dudes never realised they chain was gone until a few minutes later – the music was loud, people were hype. Between that record and and Eric B. and Rakim’s ‘Eric B. For President’ were definitely records that caught people on the dancefloor. We’re not proud of it, but at least we know the impact that record had on people.

At that time a lotta rappers weren’t really into using live instrumentation – they were kinda sticking with the Linn Drum machine, trying to get that real big Linn Drum snare and kick sound that Run-DMC and Rick Rubin were famous for and they was using with LL Cool J ‘I Need A Beat.’ We were trying not to really go that format. We wanted to make a different, unique sound, and on top of that we pinned ourselves as being “the hip-hop band,” so we had to clarify what that meant. We were really pretty proud of doing that record. Mind you, ‘Just Say Stet,’ the first single was a Linn Drum machine, and that’s when we realized, “Let’s not go that Run-DMC route.” We had to find a way to create our own style and sound so people could identify us. That’s where the name Stetsasonic came from – “Stet” mean style and “sonic” mean sound.

How did you get that spot as a DJ at the Latin Quarters?

A friend of mine – who has now passed away – his name was Eddie Bell. He worked coat-check at the Latin Quarters and he was like, “Come down to the club one night, get the feel of it.” We went down there, hung out – even worked with him in coat-check! Paradise – he was in the group X-Clan – him and this women Cassandra were the promoters, they booked a lot of the hip-hop acts to perform at the club on Friday and Saturday nights because they were friends with a lot of the rappers that were coming up like Ultramagnetic and Boogie Down Productions. DJ Raoul was the house DJ, cos the Latin Quarters was really about playing Freestyle music. Freestyle at the time was growing, you had Shannon, you had C-Bank, Cover Girls, Lisa Lisa. But they wanted to try this hip-hop thing, so Raoul played hip-hop, but he wasn’t really a thorough hip-hop DJ. He was good though.

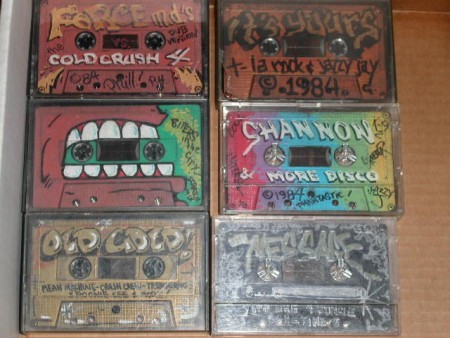

For some strange reason, one Saturday night DJ Raoul didn’t show up. He didn’t call, so people were like, “Is he alright? Was he get kidnapped or something?” So they didn’t have a DJ. At the time, Red Alert was the special guest DJ every Friday night, but Red Alert never got there ‘till 1 o’clock cos he would do his radio show on KISS-FM from 9 pm to midnight. Raoul never showed up, so I said, “Yo Paradise, I DJ, I know how to spin.” He was like, “Bet. Go in the booth and hold it down ‘till Red ALert come.” I got on those turntables, and I remember pulling every record that existed back in that time of 1986, from Mighty Mike and the MC’s [I assume he means Mighty Mike Masters], Classical Two’s ‘Rap’s New Generation,’ Kool Moe Dee’s ‘Go See The Doctor’ to Heavy D’s ‘Mr. Big Stuff,’ Biz Markie ‘Nobody Beats The Biz. Is said, “Let me play every record that is gonna get this joint jumping.” Red Alert came in and said, “Who’s the guy deejaying?” “That’s Bobby from Brooklyn!” Red Alert was really surprised to see the dancefloor was packed. I said, “Yo Red, go ahead! You gotta DJ now.” He’s like, “Nah, man. Whatever you’re doing? Keep doing it! I’ll let you know when I’m ready.” That was Red Alert giving me, “You doin’ your thing. You keep rolling.” I kept that job from ‘86 to ‘88.

What was your DJ name?

Brooklyn Bobby! [laughs] So this way it would let people know, “Oh, that’s Bobby from Brownsville!” So no one else could steal your name or steal who you are. Everybody had the same names – you had Kid Flash, Flash this – I couldn’t use Flash, everybody was already using it. So I figured out the three B’s – Brooklyn Bobby from Brownsville. That was my DJ name.

What were some of the best performances you saw there?

The first hip-hop show the Latin Quarters gave was Heavy D and The Boyz – at least on a Friday and Saturday night. After that, Boogie Down Productions, Scott la Rock and ‘em came and did ‘South Bronx.’ That’s when the MC Shan and KRS battle was going on. When they performed that night, everybody was in the house. I have a photo of me and Biz Markie backstage. That was the same night that Grandmaster Melle Mel challenged to battle KRS-One. At the time, KRS-One was coming on his heels and Melle Mel was supposed to have been king back then! He was in the movie Beat Street, he had the hottest record out – ‘White Lines’ – he was supposed to be the king! I have to be honest – KRS-One smoked him! He was young, he was fresh. That was also the night Melle Mel disrespected Biz Markie. He called Biz Markie “Magilla Gorilla.” Melle Mel was goin’ after people! [laughs] Biz never challenged him, he left it alone. He didn’t want to get into that sort of stuff.

Eric B. and Rakim, when they’re second single got released, they used to have a crew called The Strong Island Crew. There was this guy, he was actually the original 50 Cent, who 50 Cent patterned himself after. He wasn’t mentally crazy, but he was this gangster who just didn’t care. His whole thing was to protect his boy Rakim. But you protect someone if they’re in danger – you don’t start the danger. 50 Cent used to start the danger! He would go in clubs – like if someone had a fresh pair of Pumas on, he would tell his boys, “Yo, I’mma go get that guy’s sneakers, and when I get the sneakers meet me downstairs.” He would literally go rob the guy while Rakim and them’s performing on stage. That was his moment to rob people. He passed many years ago, but everybody got someone a part of their crew that’s out there. When rapper’s travelled back then, we called it a “heavy posse.” I remember 50 Cent started something in the club and Eric B. and them couldn’t even finish their show. There was no shooting involved back then, this was basically taking somebody’s chain or sneakers. He was that dude. Cool dude, but he was one of those dudes from the neighborhood who if you say something wrong to him a fight’s gonna break out.

Latin Quarters was set-up where all the stuff was happening upstairs, so once you got into the club you would have to go up a flight of stairs first with some mirrors, you make a left and you go up another flight of stairs with some mirrors and then you enter the club. Latin Quarters was a fancy club back in the 40’s and the 50’s where they had a lot of jazz and Frank Sinatra and them, so it was a sophisticated club. I remember seeing everybody running out of the club – Full Force, UTFO – because a fight really broke out during one of Eric B. and Rakim’s performances. Public Enemy did they first show at the Latin Quarters on a Wednesday night, and nobody liked them. They were booed. And again, here comes Melle Mel! All the new groups that was coming out, ain’t nobody was taking his spot. He’s the king! Melle Mel was takin’ shots at Chuck and that whole group. The audience was quiet, cos nobody knew what they were doing, and he screamed out at the S1W’s “you fake G.I. Joe dolls!”

The thing about Mel is he didn’t stay relevant by harnishing up on his skills as a writer, he kinda felt like, “People already know who I am, what I can do and what I’ve done.” So he lived more on that. A guy like LL Cool J was willing to challenge everybody cos he took the time to stay on his craft as a writer lyrically and style-wise. Mel didn’t do that, Mel kinda figured, “I’mma get up there and do the rhymes we used to do back in the days. I ain’t got to try to polish nothing!” But hip-hop was changing and cats was coming different. He didn’t drown, he just stayed in the water, floating, and he gave cats the opportunity to take shots at him.

It sounds like he was just hanging out at clubs and heckling people.

Exactly. Because that was his moment to let people know that Melle Mel is in the house. That’s how he always kept his name relevant. KRS-One was pretty new – who better to heckle than somebody with a hot record out? So Mel knew what he was doing by trying to stay relevant by challenging these people, but kinda got lost without staying sharp on his skills. I was there that night that Mikey-D and Melle Mel went at it. That was priceless.

Part Two coming soon…