![Pretty Tone Capone with Real Live]()

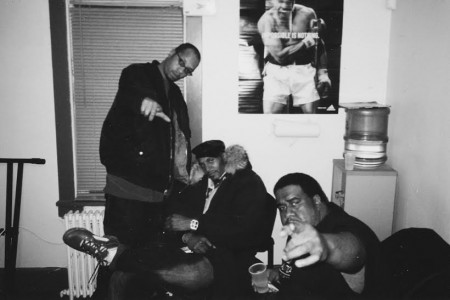

Pretty Tone Capone in the studio with Real Live, 2004. Photo: richdirection

The infamous Pretty Tone Capone from Harlem’s Mob Style is about to return to the rap game. While I haven’t heard his new material yet, his work with the group and as a soloist has given us some of the most authentic street rap possible, as well as some amusing N.W.A. diss records. Tone discussed how he was born into the hustling lifestyle in Harlem, why Tim Dog almost got scalped and explains how drug dealers are the trend-setters that rappers want to be.

Robbie: What can you tell me about growing up in Harlem?

Pretty Tone Capone: Harlem was all about money. Hustlers and stick-up kids – everybody else was workers and people in the way. Young kids getting a lotta money – doing whatever we wanted to do, where ever we wanted to do it at – at whoevers expense. It was wild like that back then. Rapping was something we did for fun, after it took off, ‘cos the public liked it. We were the only – the only – cats that were in the studio having fun rapping. There were many real cats out here, but they wasn’t rapping.

How old were you when you got involved with the street life?

I was born into this here, man. I’m from a long line of gangsters. I’m from the hustling tree of Harlem, which is from the hustling tree of the world. Family members and all that, I was raised among them. I didn’t have to go that route, but I chose that route. I’m also very intelligent – I coulda been [a] top Goldman Sachs official or one of them [top] 500 company running guys. More or less I chose this life and I love every minute of it, regardless of the down pits and downfalls.

Why did you chose that life? For the rewards it can bring?

I was lavished with these gifts, my whole upbringing is bosses – legends. I go back to Small Pauls, Nicky Barnes, Guy Fisher – they’re all just family! This is no salt eatin’ nigga buyin’ DVD’s talking about, ‘Yo! Look at these…’ – family! When I was young, ten years old, I’d cross the street for ‘Preme [Kenneth ‘Supreme’ McGriff], they’d stop at the lights, give everybody with me twenty, fifty dollars. Everybody! ‘Let’s go to the movies!’ Whatever I wanted. I was small, but also incredible at school, so I coulda went either way. But I chose this route.

What was the next step once you decided to commit to hustling?

I was established at a very young age – thirteen, fourteen. Taking trips off the brick, get rid of it off the side. Takin’ about a hundred and twenty grams, putting cut back into the kilo. Re-rocking in the vice grip, after watching them when I was young. I was making a couple of stacks when I was young. And that was my side money! I was raised around this. A hundred thousand in the drawer, used to be a running house when I was young, so I never stole no money ‘cos I got what I wanted to get. I was raised around this and became real enamored with that lifestyle and the riches and the bitches that it brung and accumulated.

When was your peak in regards to that lifestyle?

Always on top of the game, always eating. That was my downfall for not rapping – I was getting too much street money, so I didn’t think rap was equally refreshing at the time. I always kept that dirty money on me.

So you were just rapping to justify all the money you had coming in?

Exactly, I was life parole, so when I came home I sold music to camouflage my dealings.

What charge had you served time for?

That was controlled substance, of heavy, heavy, heavy amounts. ‘A’ felony, that’s the top felony in the world. That, kidnapping and a couple of other choice crimes. When they hit me with that and wanted to take the house away from my family, I copped out. I didn’t wanna get them involved with none of that.

So once you started doing music while keeping one foot in the streets, how long did it take for you to be able to get out of that life?

Over ten years they had me on life parole. I was still doing my thing, but I was kinda respected on the parole board so when I came in I never had to wait, I got a little leniency. I mighta had a ‘dirty dick’ once in a time – which is dirty urine – and it was nothing, they brushed that off. Then I’d straighten-up and I’d be good for another year or two. I might violate, catch two years – I was catching cases here and there after that too – but I was good. I feed over a hundred people, CEO of what I do.

How did you first connect with the rest of the crew?

I ran into Azie – the original, not the rapper from Queens, get that straight – through street manoeuvres. I met him through Rich Porter, god bless the dead. I met the crew that he was with, we settled in, became accustomed to each other. Did a little business, got to like each other hanging out and I joined that team. I was out amongst many teams – from Queens, Brooklyn – but this was my main team, my Harlem family. Mob Style – they wasn’t rappers at first.

How long were you running with them before the music?

I was on the run – I had a case out in Queens. An ‘A’ felony. So I packed up and came back to Harlem. I was out in that Far Rockaway, Redfern area – Nassau county, the border of Far Rockaway. Caught a case out there, so I came back to Harlem. When I came back to Harlem, I laid down tracks on 8th Ave. I had a couple of spots – they’re called trap houses now – to myself. I was doing some business with Rich. In between all that, I met Azie.

Is that when you recorded The Good The Bad and The Ugly?

No. I was a fugitive, so I set-up shop in Harlem. We established out here, grabbed a couple of spots and I met A through the Harlem vibe. They had their shit poppin’, I had my shit poppin’. We met up, we became family. In between a couple of years with the Mob, doing what we do out here in Harlem, I did eventually get caught, I got snatched up. I was going back and forth from Baltimore to Washington and sneaking back into Long Island, Far Rockaway area. Two years later, after doing what we do out here heavily, I got caught. I ended up having to do some jail time. The music didn’t start until after I came home from jail. I was shocked they was in the studio! When I went in the studio with ’em, that’s when the Mob Style era really began. They had two songs already. ‘Mob Style’ and ‘Blowin’ Up.’

Why did you want to rap?

That was something we did for fun. We were in the street, getting money hustling. Mob Style was a family on the street in Harlem, New York. We were kinda running the streets out here and in our free time we played around in the studio. This is how we felt. After hearing N.W.A. we just said, ‘Fuck it, let’s have some fun.’ We just started having fun with the music, we were basically street hustlers.

So you wanted to expose N.W.A. as phonies? Was that your inspiration?

Not really. I was in jail – when I came home they had two songs already done. That’s when I got introduced to N.W.A., ‘cos I didn’t know nothing about them until I came home. I seen a picture and I was like, ‘Who the fuck are these guys?’ So we had a little fun and went in the studio and gave ’em a piece of what we was. We was basically street guys getting money to go to the studio and have fun, so that’s the part that we came up with.

Had you been rapping previously?

No. I was on the humble, just having fun, counting money, making moves in the street. Everybody in the studio – Azie, fellow Mob Style guys – we laid it down, streets was loving it. I was just being me, talking that talk. That’s just who I am. I stumbled upon rapping – rapping was never my forte.

I’d always assumed that you were more serious about rapping than the rest of the guys, since you had a better flow.

Not necessarily. We was all having fun, and I was just a little more wild. So when you heard me, you felt me. That was me, that was my inner person – what a real soldier was doing out here in the street. Nobody was inspiring to be rappers. When Rick Rubin heard me, he wanted to sign me. That’s how that thing all started with me. I did one album, the Mob Style joint, we did that just having fun. The streets ate it up and started loving it, but we were getting more money in the streets. You see us as friends of whatever, but we were the guys to see at that time.

When I came home I was on life parole, I had a life sentence. I was facing twenty five to life, so I copped out to a lesser bid. Three to life – I copped on that. ‘Gimme two of those!’ I couldn’t wait to get that. So that’s when I came home. We started the Mob Style music vehicle, after Azie got shot and all that. He was in jail when he went through that shooting in the Bronx and all that. You saw the movie Paid In Full, right? That was Azie that got shot! I was upstate in jail when that happened. They sent me newspaper clippings. I was fucked-up when that happened.

How did Rick Rubin reach out to you?

We met at The Marriott, the [New] Music Seminar back then, through a friend from the Far Rockaway area – Casual-T. He was working with Hollywood Basics [sic], Tupac and them. He set up a meeting with me and Rick. I just got home on life parole, I seen a real good opportunity for me to have no excuses of why I got all of the jewelry and the cars I had – a music contract! I wouldn’t have to get a job, so I was thinking from a criminal mindset. So I hopped on that and took that deal.

Were you still operating out of New York when you signed that deal?

Yes. They flew in once or twice, we met face-to-face and then everything else the lawyers took care of.

What was the story with the ‘Case Dismissed’ video?

That was something I just threw together, I did the treatment for that. I was disappointed at the quality of the cameras they was bringing me, so I lost all enthusiasm for that video. But I still went through with it and we just made it what it was. We were having fun, that’s all that was.

Did you record an entire album for Def American?

I recorded about twenty five, thirty joints – all crazy – but Rick didn’t know the impact we had on the streets. [Tone’s producer Fred Flak discusses these vaulted tracks in this Martorialist interview from 2011]. Streets wasn’t a real heavy scene in the music industry at that time – everybody was rappers with gold chains. We were the hustlin’, real dudes, but he didn’t know this was the wave of the future that we started. He was sitting on my shit and I was out here making more money in the streets. He didn’t know what to do it with it, I made him release me ‘cos he ain’t put it out the way I wanted it put out. That marriage dissolved.

Do you have any of that unreleased material?

I’m quite sure Rick has all that in the library. My publishing’s intact, so if he wants to use it I’ll let him put it out, down the line or whatever. I just washed my hands of the industry at the time. Puffy was hollering at me at the time too, right when Big just started. I remember I was in his office, he threw on ‘Party and Bullshit’ and asked me what I think about his new artist. He was getting his hair cut in the chair, up at the label. I was caught up in the streets, so…

What did you tell him when he played you the Biggie song?

That was the only song he played for me. It was okay at that minute, that one joint that I heard, but I was on some other, real street shit – which they eventually capitalised on also. I didn’t have no time for the rap game, ‘cos money wasn’t poppin’! I was getting more money in the street – ten, twenty thousand a week – doin’ nothing.

You mentioned you weren’t happy about N.W.A. when they came out? Did you feel that they were frauds?

Nah, we’re not gonna say they was fraudulent or nothin’ like that, ‘cos we didn’t know these guys! But when I first looked at ’em, I was like, ‘Who the fuck are these guys? C’mon, these can’t be the top niggas in the streets!’ They was talking about beating bitches up, 8-balls, ‘Fuck The Police’ – which is one of my favorite, top joints, I love that joint – so we hit ’em with that drug shit, who the fuck we be! We was doin’ this out here! I don’t know what they do around the world at that time, I was kinda young and dumb. Tim Dog took that idea and ran with it, made a song – ‘Fuck Compton’ – his punk ass. We shoulda stomped him out, ‘cos he wasn’t representing New York at that time at all, he shouldn’t be talking like that.

You felt like Tim Dog didn’t do a good job with that song?

Tim Dog hopped off my idea and tried to run with it! But he wasn’t built for that kinda talk with these fellas at that time. I’m surprised they ain’t scalp him, ‘cos we was about to do him real bodily harm up here! We knew he took that, but I was in the game so we ain’t give a fuck about the music at the time. I just wanna let motherfuckers know that Dr. Dre shoulda called me, ‘cos motherfuckers know god damn well we turned their motherfucking career around. I respect Ice Cube – Ice Cube came to one of our shows way back when he was in New York. I respect they movement.

What other rappers did you used to like? Were you a fan of guys like Spoonie Gee?

Eh, Harlem ain’t never really had no top rappers. Them rappers from Harlem wasn’t really in the streets like that. They probably was doin’ they thing on they level, but the level we was on? Was nobody really on the level we was living and loving life on. To this day they still love us, but no one ever gave us the correct respect and due. Of course they won’t, ‘cos that takes away they shine, but many artists took a Kibble and Bit of styles here and there, used peoples names – all type of foul shit they shoulda been chastised for but we let slide, cos it’s life! But I’m back now, and everything will be straightened out. They thought I was dead, or locked-up for life. They ain’t hear from Pretty Tone in a minute.

Is there anyone in particular that’s pissing you off in rap right now?

No, its just the state of the game in general. I learned how to separate entertainment from reality as far as this music is concerned, ‘cos if everybody was ‘sposed to be official of what they talkin’ we wouldn’t have no music! It’d be like three albums out a year! Ninety seven percent of these guys is frauds, but some of them have good music. Some is lyrically inclined, even though they’re lying about the life they was living or what they was doin’, but we know they was bitches. They kinda tickles me a little bit too. These same faggots that be thinking they live what they rhyming about, but don’t know, but then learn the difference when you see some real motherfuckers around you. As far as the rap game is concerned, everything’s fucked-up right now. It’s terrible!

I agree. Are there any rappers who you respect?

Very few. I like Rakim, that was a friend of mine. Eric B. was my motherfucking man, he used to come visit me in jail. Kool G Rap had the slick lisp, so I fuck with him. He seems on my level, as far as spittin’. There’s only a couple of spitters – ever – in the history of music. I liked N.W.A., especially when they flipped that joint on us [‘Real Niggaz‘], got a real chuckle outta that, I liked that. I met Biggie, god bless him, I loved Biggie. I was around Pac when he was dancing with Digital Underground. We crossed paths many times, solid dude, about that black culture at the time. A lotta people get lost in this game and nobody know where they are. The game is just fucked-up. A lotta old school motherfuckers rapping, they washed-up, they finished. I don’t even know why they tryin’ to come back. That one year you had that glow – give it up, you’re finished! Get a job. I’ma show you how to do it from an old school gangster nigga! [laughs]

How did you feel about Cam’Ron and the Diplomats? Did they do a good job of repping Harlem?

I loved their production! Their production was out this world. I fucks with Cam on the Harlem vibe – a cool, good brother. I know Juelz Santana, I like him. Got some good friends I fuck with. The rest of the team’s aiht. They was holdin’ it down for they era. All this shit is watered down, to a real nigga. I bring that concentrate, straight from the tree! All they got is ‘add to,’ add this and that to get the flavor. My shit is straight flavor. I’m rough when I’m judging music, ‘cos I know what’s supposed to be and what’s not supposed to be, but them boys is alright out here. But it’s not just about Harlem, I was fucking with rappers all over!

Did you like the Geto Boys?

The Houston scene? Eh, I’m ain’t too indebted in that. I ain’t know too much about that scene, I’m a real city slicker, top ten nigga. Whatever section you from, I respect your element in what you at, and I hope you the best at it. I respect bosses from all four parts of the world – east, west, north and south. I respect the workers who try to be bosses. I respect the good guy that’s got a job, that knows his lane. I just like originality and realness, one hundred percent. I’m no judge on who’s doing what, but you cross me? You’re done. That’s all I can tell the world.

Are you still living in New York?

I’m in Virginia Beach and New York City, back and forth. Most of the time in New York City, takin’ care of a couple things.

How has Harlem changed since you were a kid?

Oh, Harlem’s finished. There’s no inspiration out here, I’m disappointed when I’m out here. That’s why I’m coming to bring new life to the neighborhood, put new Jay’s on these kids feet who can’t afford it. Put a glimmer of hope in they eyes. Let ’em see what a real boss sound like and how they move. How they manoeuvre. I’ma guide you straight. I’ma let ’em know what the game is about. When you sign up for this game? This street game, this hustling game, is anything goes! Everyone gets crossed, no love. So whatever happens while you’re in the game? You asked for it! ‘Cos if you had a job or went to school you wouldn’t be a part of it, you’d be able to walk by it. But when you step in the game? It all goes. Mother died, brother set you up, sister set you up, you kill a couple of niggas you love – anything goes in this game. That’s what I want the kids to know.

Why are you so disappointed in Harlem these days?

I travel on a different plane out here on the streets. I don’t really know what they doin’ amongst the average motherfuckers ‘cos I don’t be around average motherfuckers. I’m a trendsetter, so when I drop some fly shit it sprinkles in and hits the average motherfucker around the world – not just New York – and it wake ’em up. So I’m really just putting in an appearance for my people and dropping some flavor for these street niggas to really bounce to. Future shit is alright, but I don’t understand none of that shit he sayin’! It’s time to drop some real street shit.

Did you used to hang at spots like the Latin Quarter back in the eighties?

I did all that. I did shows with Busta [Rhymes] and all of ’em, the Palladium. We did mad shows and we weren’t even no rap niggas. Puffy used to just book us, put us on his flyer. We show up, shut it down. Joedeci, all them niggas opened up for us! The Rink, Palladium, the Apollo, we did all that shit. When we did that shit we came straight off the streets. ‘Yo, it’s time to go!’ We all just follow them down there, eight or nine whips – zoom zoom, zoom. Bronx, Queens, thorough niggas – Supreme Team, my family. The roughest and realest niggas from every borough used to come out when we came out. More or less, it was a convention for real niggas. Our name rang, brought in the tickets, filled the seats.

What was your favorite club from that era?

Wasn’t really a club person. My people, we had ‘First Million’ parties, we used to rent clubs and celebrate a motherfucker we fucking with get his first million. Big black tie affair, nothing but minks, sequins, gators. It was mostly a street affair, street niggas. We had our own section, we didn’t follow nothin’. Rooftop and the Skating Rink, those is fixtures from all over the world, back then. We was regulars up in there. But everything is everything, wherever we went is a party! Tupac used to go to Nells, used to be at Nells with him and shit.

Were you heavy in the car game?

Aww man! My team is known for nothing but the meanest cars! We started half Formula One type motherfucking car dealers right now! My man Azie and them, they was known for dressing the cars up! First big scale BVS’. We started that game! We started the car game, the jewelry game, We started all this shit. Every car from A to Z. We had three, four garages, full of cars.

Did you have a favorite model?

Nah! I liked to whip on the Benz. Azie liked the BM, when he got the 745 that time. I was a Benz man at the time. Rich and Po had the Porsches, those niggas had four, five, six cars each, switchin’ up. I had like one or two.

What about the jewelry? Did you sport the dookie ropes?

We started all that, that’s being redundant. We ain’t have dookie ropes, we had diamonds! We had gangster, mobster diamonds. Our shit was exclusive! Instead of that gaudy shit the rappers was wearing? We had that exclusive, exquisite, fly shit. That tailor-made custom shit! Pinky ring – thirty thousand. We didn’t have that gaudy bullshit. We had the four finger rings though! We started that. LL started getting the four-finger diamond rings after we came out with ’em. Po had one, I had a little baby three-finger joint. My man Chuck Barnes had one, there was a couple of niggas that had them joints. Dapper Dan with the Gucci and the MCM – we started all that shit, man. But that’s back then.

So you guys were the first to get those Dapper Dan outfits?

Yeah, we started him. We branded, opened him up. Then the rappers started going after they seen us with the fly shit. Eric B., Rakim, Mike Tyson used to come through – that’s my man too, at the time. Jesus, a lotta good dudes used to go to Dapper Dan back then. You had to have cake to come through, we used to shut the whole store down until we left – eight or nine minks, all type of shit. That was just the flavor of the day, at that time when the money was coming in.

So the rappers were just trying to imitate what you guys were doing, since you were setting the trends.

There ya go! That’s history, you couldn’t have said it no better yourself. That’s the story of this motherfucking game. Hustlers first, then the rappers wanted to be hustlers. Everybody lying like they been hustlers. Rich spinners and whipping shit up – these faggots couldn’t whip nothin’ up! They wouldn’t be safe to have a spot around no real niggas.

Are you planning on releasing new music?

Yeah. I’m the best who ever did it! I’m about to release some new shit in a minute, ‘cos I’m kinda upset at the state of the game now. A lotta faggotry goin’ on. I don’t want my sons growing up listening to this, there’s no real man music. No one condones guns, violence and drugs, but hey! This is what some people have to do in order to live! Everything don’t have to be targeted towards one thing. If you’re versatile and you’re nice, you’re gonna drop and be hot regardless. Everybody’s got a gimmick, so I’m not really impressed with the state of the game. I’m comin’ to kidnap it!

This is for the documentary/EP. I’m about to smash ’em with three classic Mob Style joints – ‘Gangster Shit,’ ‘I Play Rough’ and like five or six new joints. I’m about to smash these clown back to normal and show ’em let ’em know how real men do out here. There’s a lotta frontin’ out here, a lotta acting. You don’t wanna lead the kids down the wrong path, you wanna hear from someone who’s been on that path. These guys are sweeter than tea!

What are some of the songs we can expect to hear?

I got a joint called ‘Point Blank’ which is a gumbo of what I’ve been hearing the last couple of years from these clowns. I chewed their shit up and spit it back at ’em in the fashion it shoulda been spit. It’s mean, they love it out here. I got a joint ‘It Was You,’ that’s a joint with Jadakiss. An up and comer from the Bronx, Main Scrap…Mike Boogie. So when I drop this new music, bop your head, have fun, pop bottles. I only came here to have fun with y’all, ‘cos I wasn’t approachable for many years. Now I’ma let my hair down and have some fun with y’all motherfuckers out here.

Do rappers like Rick Ross piss you off? Or do you not really care?

I’m a little mature now, so I separate reality from entertainment and all the gimmicks that these brothers bringing. Lyrically, that fat boy can spit, he put his shit together. I’m a spitter, one of the best ever! I don’t know if Puffy opened up the Biggie vault and let him get the formula and he ran with it, ‘cos he’s not a dumb nigga, he sound intelligent. He think he that nigga, so sometimes when he spit it he sometimes sounds like he might really think he’s that nigga! He’s spittin’ heavy, he’s probably one of the top spitters from a lyrically standpoint, regardless of if he was police or not – it’s entertainment, and I gotta tell myself that. ‘Cos if I don’t? I don’t like nobody!

Just watch, I’ma re-establish the game, show these fags how to spit realness – I’m just gonna tear it up. These are cartoon, cornball, paper gangsters. I want my kid to know what realness sound like and feel like, and the other kids aren’t sacrificing they lives, listening to these faggots who aren’t doin’ nothing but living in a condo, selling poison to my peoples who’s out here doin’ that shit, losing their life and freedom. I’ma show ’em the realness of this game and give ’em the combination of how to get outta here!

So you want to let people know the good and bad sides of the game?

The pros and cons. The only pro is if you’re getting money and are successful. Anything else is bad news. If you ain’t getting no money, it ain’t worth it. There’s nothing for you but death and jail if you a stupid hustler. Now, if you’re hustling to get out your predicament, you know how to make the moves and business transactions and make something good outta that? You get away from that before it gets too hot. There’s nothing but snitches out here, that’s why the game’s fucked up – snitches! I speak from the heart! We don’t gotta bite my lip for nothing! Whatever I said, I stand by it.

Special thanks to Stan Ipcus and Tone’s nephew Bobby for making this happen.

Pretty Tone Capone – ‘Kidnapped‘

Pretty Tone Capone – ‘Marked 4 Death‘

Pretty Tone Capone – ‘Across 110th Street‘

Pretty Tone Capone – ‘Can’t Talk Too Long On The Telephone‘